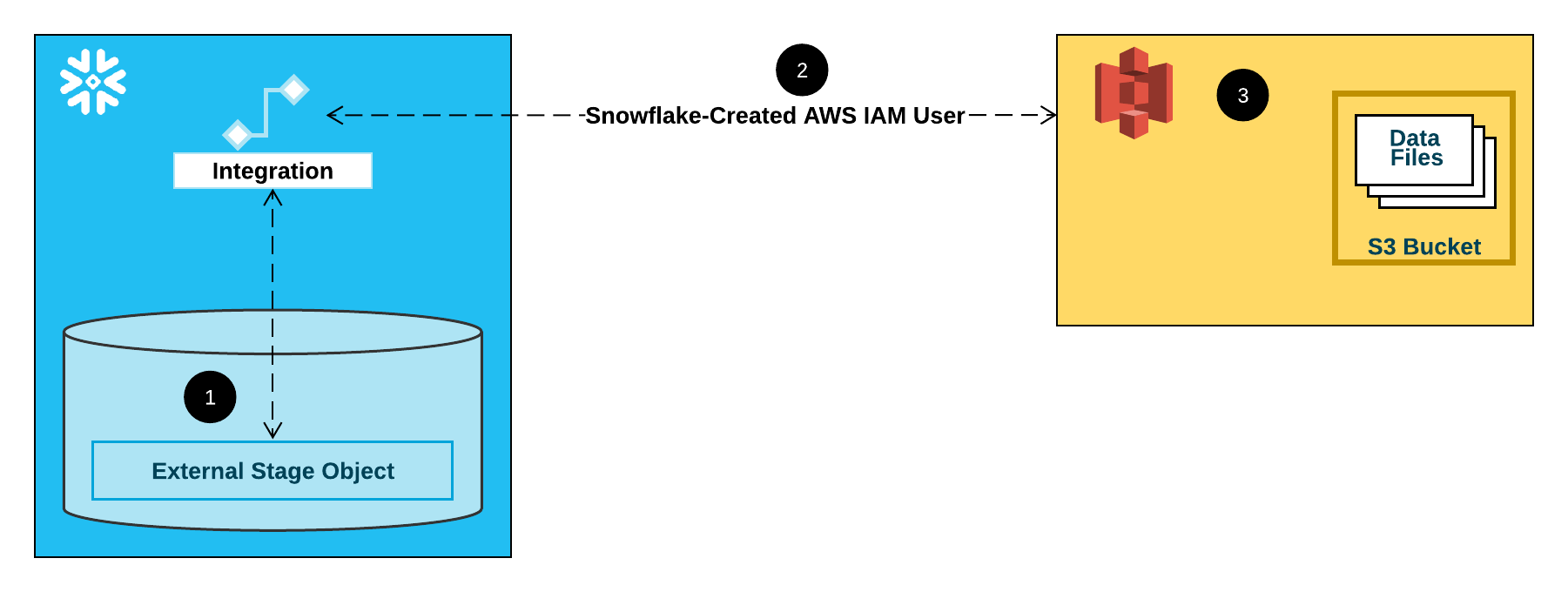

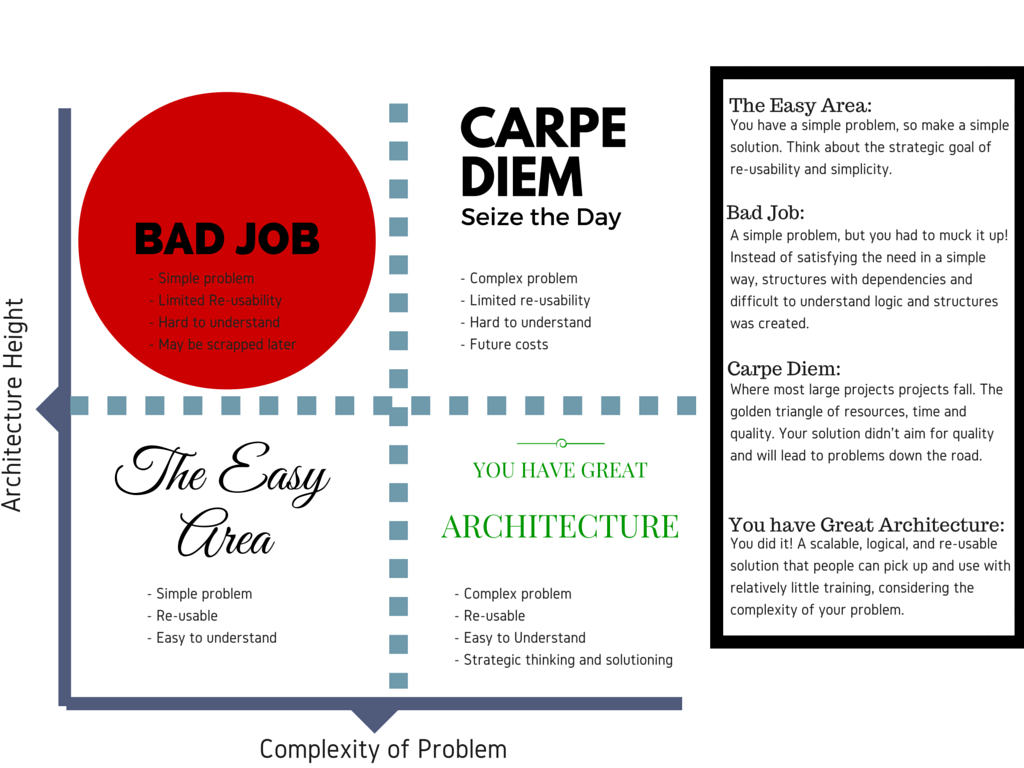

In this final post, we’ll go over the final implementation of this serverless data ingestion pipeline. What is the result of all the effort put forward to build this serverless data ingestion process? I think the best way to break this down is to compare what we were originally aiming for, and what was implemented. Below you can see diagram that was created in the post outlining the overall architecture.

The usage of AWS events to kick off Lambda functions was extraordinarily easy, and there’s plenty of good documentation to get started. The S3 event passes through all the metadata needed to parameterize and operate the pipeline in JSON. The documentation from Amazon, makes it super easy to access and use when setting up your Lambda functions.

Below you can see the actual code executed in the Lambda function. Notice that the variables bucket_name and file_name are both retrieved from the event.

from classes import ingester as ing

from classes import forstaparser as fp

def lambda_handler(event, context):

bucket_name = event['Records'][0]['s3']['bucket']['name']

file_name = event['Records'][0]['s3']['object']['key']

target_bucket = 'landing-bucket-11.15.2021'

upload_table = 'landing_table'

source_type = 's3'

if bucket_name == target_bucket:

upload_file_name = ing.ingester.convert_object(None,bucket_name,file_name)

raw_logs = fp.parser.read_logs(None,source_type,target_bucket,upload_file_name)

fp.parser.dynamo_landing_load(None,upload_table,raw_logs,file_name)

else:

landing_ingester = ingester.ingester()

landing_ingester.copy_bucket(bucket_name,target_bucket)

#test_parser.t_parser()

print("Completed")Put simply, the function does the following. First it receives the event metadata, parses through the JSON, and obtains the bucket name that we want to transfer the files from. Notice we can point to any bucket, and it will always drop the file into ‘landing-bucket-11.15.2021’. Using the event metadata means I can reuse this Lambda function as often as I want to create a central dumping ground for staging data to be loaded.

Second, once files are put into ‘landing-bucket-11.15.2021’ another event kicks off. This event cleans the data, ensuring proper encoding (UTF-8), and then loads the data into our DynamoDB landing table. All in all pretty simple.

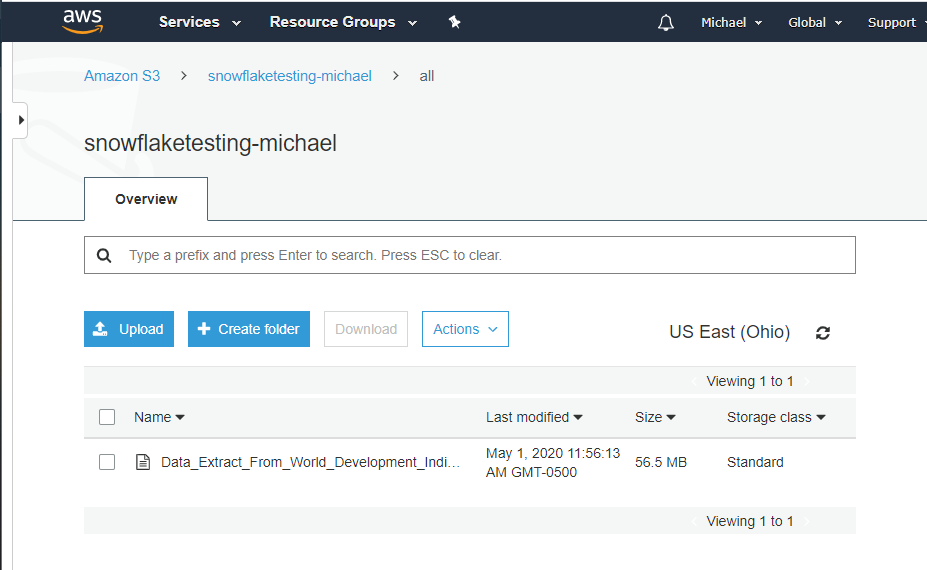

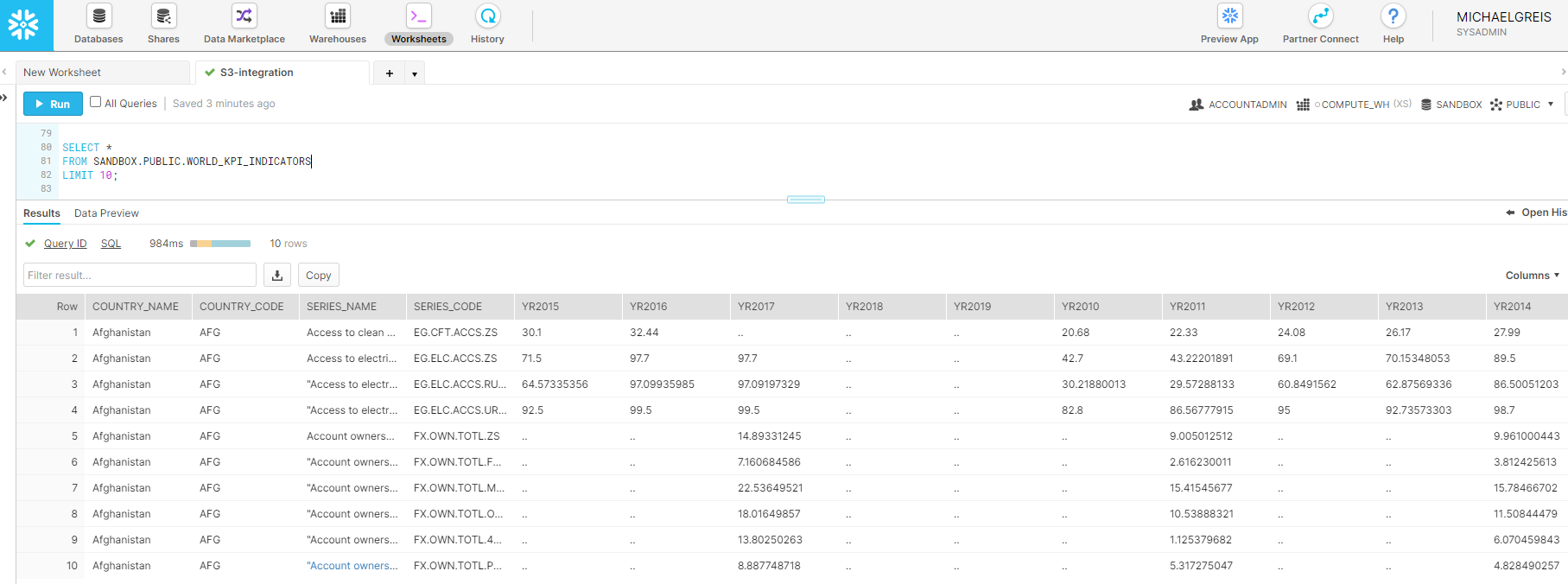

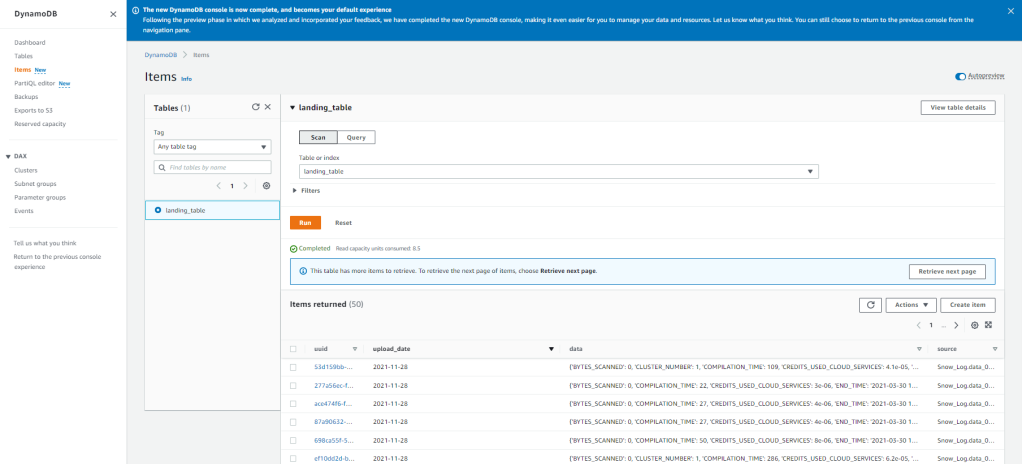

Below you can see everything running in action.

As we can see above, the files were automatically copied, and for posterity’s sake, we can check the cloud logs to see we have a 100% success rate in the last hour. Looking at the below we can see the result of 100% successful executions for our first Lambda function.

The next step is automatically kicked off whenever an object is PUT into the ‘landing-bucket-11.15.2021’ and loads the data into DynamoDB. With the current setup, we can see the data uploads successfully and the data is now available in DynamoDB to be ingested into whatever processes/analytics we want! The best part being that once this is setup it is automated, and auditable going forward due to the tools AWS offers.

In order to build this, it may not have seemed like a long journey. But keep in mind, in the process of building this little project out I’ve had to pickup and learn quite a few tools. Docker, Lambda, S3, IAM, Python, Boto3, and a few more tools which we’ve covered in the previous posts. If I need to do this again, it’ll be much simpler based upon what I’ve learned.

- Architecture: What’s the approach?

- Development Process: How did I set up my environment that was effective and efficient for developing?

- Difficulties: What issues came up, and how did they get resolved?

- End Result: Does this architecture achieve the goals that it set out to achieve?

Thanks for reading along!